Dominion Atlantic Railway Digital Preservation Initiative - Wiki

Use of this site is subject to our Terms & Conditions.

Kings County Register August 3, 2006 - Berwick Evaporator Plant

For search purposes, the text of this article is shown at bottom.

Museum tracing evaporating Valley apple history

Kings County Register, August 3, 2006 7

>Dan Conlin

Apple Capital Museum Society

It was once a vital industry in the heart of Berwick, a sprawling complex created by a would-be empire builder with the tallest smokestack in town. Today, remarkably few traces remain of the Berwick Evaporator.

Volunteers at Berwick's Apple Capital Museum are attempting to build a model of the evaporator plant which once stood across from the Berwick Frenchy's.

Evaporators turned apples into dried apple slices. Lightweight, needing no refrigeration and keeping for years, dried apples were popular for remote settlements, lumber and mining camps and the military. Evaporators were an important attempt to generate extra profits and jobs by making a "value-added” product from the Valley's apple crop. They also provided an important market for smaller and lower-quality apples not suitable for the Valley's dominant fresh-fruit export market.

Evaporators, along with vinegar plants, were forerunners of the large central processing plants such as Graves, Scotia Gold and Great Valley Juices. There were once dozens of evaporators across the Valley but, today, none survive. The Valley's last known surviving evaporator building, in Kingston, was demolished around 2000.

Berwick's evaporator was one of the biggest. It was built about 1919 by Robert J. Graham, an ambitious businessman from Belleville, Ontario. He tried to take control of the Valley's apple manufacturing, buying out and building evaporators from Bridgetown to Windsor. In Berwick, he built a large factory, complete with its own adjacent fruit warehouse and railway spur line. Unlike most of the Valley evaporators built of wood, the Berwick evaporator was built from concrete blocks to avoid the frequent cataclysmic fires which engulfed evaporators when the furnaces used to dry apples set their wooden structure ablaze.

Graham's evaporator was large two-story building, later expanded to three-and-a-half stories, surrounded by a large loading bay to receive apples and load the finished product onto boxcars. A rail line almost 1,000 feet long was specially built from the mainline of the Dominion Atlantic Railway to hold up to 17 boxcars. A lane built from Commercial Street to the evaporator and near-by warehouses evolved to become today's Front Street.

Inside the building, apples were pared and sliced by machinery powered by a coal fired boiler and its 80-foot iron smokestack. Roaring fires in six furnaces dried sliced apples in special tin-lined kilns, sending the water steaming out through the evaporator's characteristic roof vents. The sweet smell of heated apples mixed with the harsher smell of sulphur used to bleach the apples.

The evaporator was a seasonal operation which started with the apple crop in September and ran 11 hours a day, six days a week, until spring when the apples supply ran out. It employed a large, mostly female workforce.

Graham seems to have overextended himself with his ambitious investments in the Valley and soon ran into trouble. According to a "History of Berwick Apple Warehouses,” an article written by Robert Chute, the Berwick evaporator stood idle for long periods as Graham was forced to sell off his Valley plants.

In 1933, the Simms Company of Saint John, New Brunswick bought the Graham properties. Simms was, and remains today, a very well-known and successful maker of cleaning and paint brushes. As Robert Chute noted, "Just why a brush manufacturing company became interested in dried apples remains a mystery to me." However, Simms made a better go of it than Graham and the evaporator proved an important source of work, especially for women, in Berwick through the 1930s.

The evaporator assumed an even more important role in World War Two. Wartime shipping restrictions cut off the Valley from Britain, its biggest market. Evaporators, along with juice factories, were one of the few remaining customers for the bulk of the Valley crop, as they produced large volumes of apple by-products as wartime rations. Workers struggled on the loading dock receiving vast numbers of wooden apple barrels. Traditionally built for a single one-way trip across the Atlantic, the barrels in wartime went back and forth from warehouses to evaporators until they fell apart, as hoops broke and staves swelled. "It was enough to make a minister swear," recalls Robert Chute.

During the war, Simms sold the evaporator to R.A. Parker and Sons, In 1945, the United Fruit Companies briefly owned the evaporator plant, before selling it to Roy Joudrey of Hantsport. The Valley's apple industry never regained its former glory after the wartime loss of the British market and the Joudreys switched the plant to canning pears. The leftover pear juice was drained off into a holding pond behind the plant. A humorous incident occurred when a worker was asked to cut a small channel so a trickle of pear juice could drain into a nearby ditch. However the trickle quickly turned into a torrent, flooding much of Front Street with a sticky wave of rancid pear juice, much to the annoyance of neighboring businesses!

Eventually, the pear operation was closed down and the old evaporator stood silent for a number of years until it was purchased by John Palmer of Morristown. He demolished the building sometime in the 1980s and the site is now used for parking and building materials by the Berwick Home Hardware.

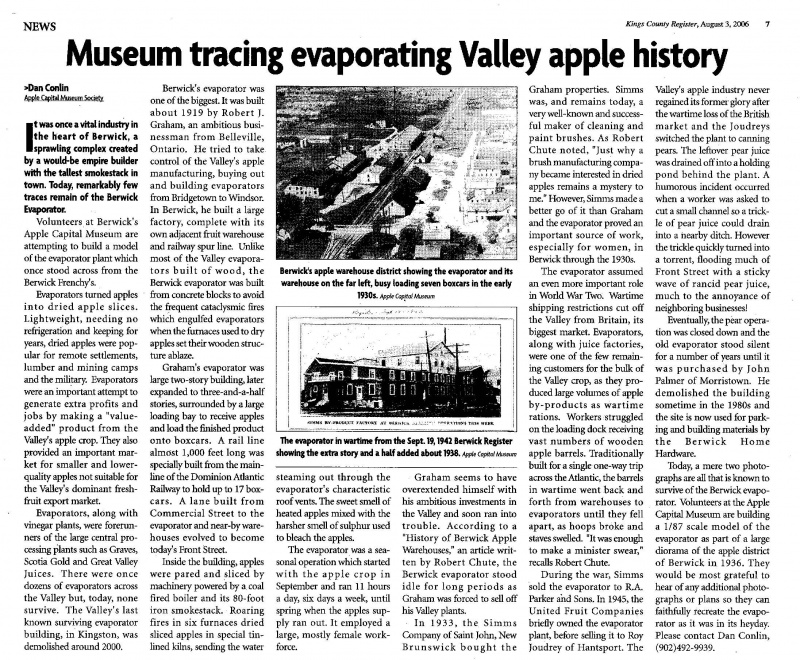

Today, a mere two photographs are all that is known to survive of the Berwick evaporator. Volunteers at the Apple Capital Museum are building a 1/87 scale model of the evaporator as part of a large diorama of the apple district of Berwick in 1936. They would be most grateful to hear of any additional photographs or plans so they can faithfully recreate the evaporator as it was in its heyday. Please contact Dan Conlin, (902)492-9939.